(Photo above by Yvonne Ng)

My employers’ observations were always the same: “You don’t look like you want to be here.” And it was true—they saw what they thought they saw. For someone entering the field of health care, who felt powerfully driven from childhood to care for the underserved, abused and forgotten, I could not seem to convince anyone—myself included—that I actually liked people.

One day, my sibling, Addison was receiving the Gohonzon—some mandala, I gathered, that Addison would be taking home as an important step on their journey in Buddhism. I went to protect them from whatever it was they were getting into. But when I arrived, I found a diverse community of warm, unpretentious people familiar with one another’s lives. A young woman shared her experience of using faith to transform the resentment she’d felt toward her father. That inner transformation rippled out, eventually turning family strife into harmony. Featuring neither saints nor heroes, her story was of a young person who’d felt broken, used faith to get in touch with her heart and decided, based on the courage she found there, that she would be the one to heal.

And I found myself fighting back tears—baffled and even annoyed to be disarmed in a setting like this—this group of total strangers.

Afterward, I turned the meeting over in my mind, scanning my memory for some overlooked threat. I couldn’t find one. In secret, embarrassed that I was willing to try, I started chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo a little each day. Slowly, reluctantly, I began to check out my local Buddhist meetings.

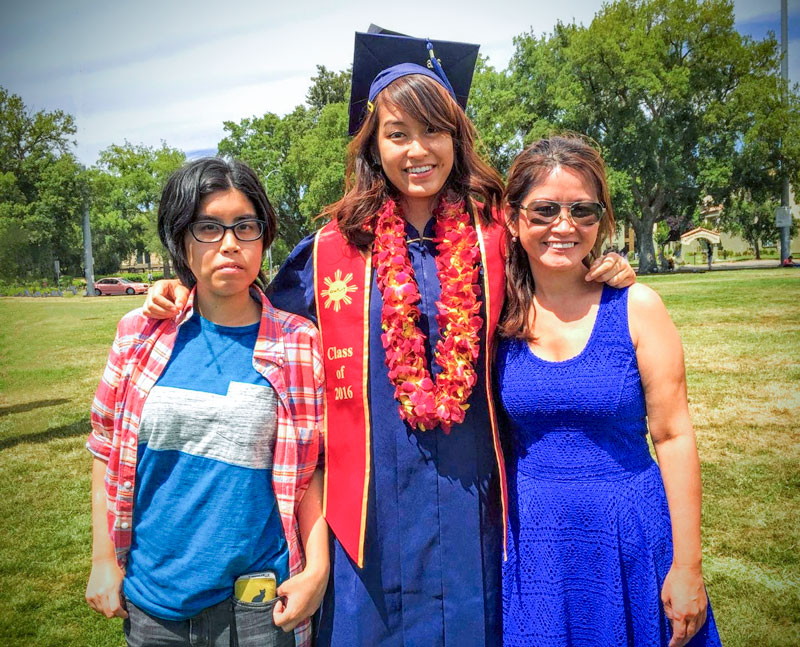

Daisy Prom with her sibling, Addison, and mom, Suzy, at her college graduation, Davis, California, 2016.

The meetings made me uncomfortable because I couldn’t stand the praise. I wasn’t used to it, I didn’t believe in it and, most importantly, I didn’t—or couldn’t—hear it.

Authentic praise was simply, at that point in my life, the opposite of what I’d known—in my family and in the working world.

Things really got tough when I began supporting meetings behind-the-scenes, where I received not only praise but also constructive feedback. But the members patiently met with me to chant and dialogue about whatever was coming up in my heart and studying the writings of Daisaku Ikeda and Nichiren Daishonin to learn more about the Buddhist perspective on my life.

This too, was uncomfortable—it was such a different response to my negativity than I’d received elsewhere.

Slowly, very slowly, I managed to relax into a different kind of listening, to trust in what this Buddhism taught. I engraved the followings words of Nichiren Daishonin:

Arouse deep faith and diligently polish your mirror day and night. How should you polish it? Only by chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo.

“On Attaining Buddhahood in This Lifetime,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 4

As I deepened my understanding of Buddhism and directed my energy toward encouraging others, my defenses, geared toward protecting myself, began to thaw.

A turning point came in 2020, in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. I was supporting other youth in my neighborhood but I had no idea what I was doing, really, and was sure they’d see this the moment I opened my mouth. But one day, I got a text in a loop from a few of the women in the area, updating one another on something unfolding in the neighborhood.

The mother of a young woman had contracted COVID, and the daughter, struggling for weeks with anxiety and depression, was too anxious to leave her house for groceries. The women acted swiftly, checking in. As all this happened, I was overcome with shame—if anyone ought to have checked on her, it was me, but I’d been too stuck in my own head.

After this, I began reaching out, then meeting regularly. If she was struggling, I’d ask if we could read something that had made me feel better, and we would—something from Daisaku Ikeda or Nichiren Daishonin. I began chanting for her happiness ahead of our visits, for her to overcome specific challenges and achieve specific goals. Without realizing it, I found I was able to be for her the person I was at the center—positive and warm. In time, she responded in kind, brightening up and getting more involved.

From here, I began to carry my Buddhahood into the fiercest arena of my life—my work as a nurse practitioner. As usual, I was the last person to recognize the changes taking place in me. Within the year, I was hired onto a new team, for a huge raise, into the highly competitive role of an inpatient psychiatric nurse. After the hire, they told me that they knew, upon interviewing me, that of the over 100 highly qualified applicants, I was the one they would be hiring onto the team.

Later on, these same colleagues would nominate me for the prestigious DAISY Award, almost unheard of for an inpatient psychiatric nurse, whose patients are often admitted in crisis, for short, intensive stays. I was stunned to hear my co-worker say that she’d begun to ask herself in difficult situations: What would Daisy do

It was beginning to dawn on me that I might be worthy of calling myself a bodhisattva. I found myself more able to listen with the ears of the Buddha, to hear praise and believe the person who’d given it. I even allowed myself to be impressed by certain, previously unimaginable improvements—the end of my recurring nightmares, for instance, or maintaining calm when a situation was beyond my control.

And then, all this inner work, all this progress, collapsed like Jenga blocks in the winter of 2020 when my boyfriend, on the eve of his 30th birthday, was diagnosed with an aggressive form of cancer. Immediately he began chemo and was reduced to a shell of the person I loved, hardly able to move or speak. There seemed to be nothing I could do to help him. And this helplessness sent me spiraling.

Chanting through tears at the foot of his bed, I began to realize that I had to find a way to take care of myself to have any chance of taking care of him. This prayer for others was what gave rise, eventually, to the awareness that I needed support myself. Somewhere in the winter of 2020, for the first time in my life, I sought professional help and learned that I had complex PTSD, something I initially rejected. “You’re thinking of my parents,” I told my therapist. “They’re the ones who fled a genocide. Not me.”

My parents met in the United States, years after fleeing Cambodia as children. Both had watched countless loved ones die before their eyes, sometimes in their arms, most often from starvation and dysentery. “Worse than bullets,” my mother always insisted. “The most horrible way to die.” Both carried the guilt of survival, as though it were the dead, and not they themselves, who’d been abandoned and left behind.

They’d been children then, too small to protect the people they loved. For my father, in particular, that pain had become a rage that could tear through the house like a fire. Often, I’d watch, too small to be of help to anyone.

It was always an argument between my therapist and me—my therapist prodding, me denying. But between our conversations, I was having other ones—with friends in faith and with myself in front of the Gohonzon. Between these, there was something I began to understand—that the negative voice that could come tearing through my mind, was not mine.

I remember a talk I had with a fellow member in 2021, soon after my boyfriend’s cancer was deemed in remission. I mentioned the negative inner voice that I’d thought I’d begun to overcome but that had attacked me so viciously throughout my boyfriend’s recovery.

She listened and then told me that she’d had a similar voice once. It was only after several years of Buddhist practice that she identified that voice as her father’s. She suggested that when I hear the voice, to open up something from Ikeda or Nichiren Daishonin and replace it with a voice of encouragement.

I began to do this and then chant, internalizing what I’d read as something addressed to me directly. Slowly, the abuse that I’d assumed was “baked into my DNA” began to unfuse from the depths of my life, and I began to engrave Ikeda’s praise in its place.

To my surprise, this continued to impact many aspects of my life, showing me that I wanted to also pursue a new career.

I began for the first time to include my own happiness at the forefront of my prayers.

I began for the first time to include my own happiness at the forefront of my prayers. Many emotions arose—in particular guilt at the prospect of leaving my current colleagues and patients behind. But the more I chanted about this, the more strongly I felt that to enter a new chapter of my career, in a setting that did not retrigger my traumas, was not failure. If I was to help others become happy, I myself had to become happy. And I deserved this, to feel safe and protected at work.

Last December, I landed a job that answered my prayers to a T, with another huge pay increase and a supportive team. It took me another half a year to begin to fully internalize that I deserve this level of appreciation, safety and pay.

And remember that young woman that I mentioned who I supported? Total turnaround. I remember clearly a Buddhist meeting she emceed at the end of 2022, where a woman in her 90s was attending for the first or second time. Apparently, this elderly woman had been suffering for years. “I’m over it!” she proclaimed, by which she meant life. That’s when that young woman piped in and brought up how she’d been depressed once too.

“I was working at McDonald’s,” she said, “and I remember staring at the fry oil and wanting to throw myself in. But then Daisy started visiting me and I started chanting and feeling better. If you chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo and keep at it, you’ll feel better too!”

I was stunned when I heard this. I hadn’t realized that I’d had that kind of impact. In any case, that woman, she since received the Gohonzon, having begun to feel positive inner change.

You might think there’s no hope of transforming yourself or your situation. But when that inner negativity arises, you can let it run its course or you can fight it, chanting until you believe in the depths of your life that you deserve happiness and are capable of creating it.